Thursday, March 6, 2008

$100 oil fuels tax flap over Big Oil, renewables

Top Iraq contractor skirts US taxes offshore

CAYMAN ISLANDS - Kellogg Brown & Root, the nation's top Iraq war contractor and until last year a subsidiary of

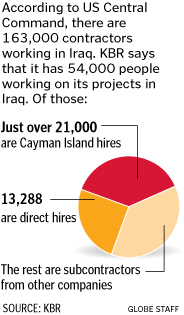

More than 21,000 people working for KBR in Iraq - including about 10,500 Americans - are listed as employees of two companies that exist in a computer file on the fourth floor of a building on a palm-studded boulevard here in the Caribbean. Neither company has an office or phone number in the Cayman Islands.

More than 21,000 people working for KBR in Iraq - including about 10,500 Americans - are listed as employees of two companies that exist in a computer file on the fourth floor of a building on a palm-studded boulevard here in the Caribbean. Neither company has an office or phone number in the Cayman Islands.

The Defense Department has known since at least 2004 that KBR was avoiding taxes by declaring its American workers as employees of Cayman Islands shell companies, and officials said the move allowed KBR to perform the work more cheaply, saving Defense dollars.

But the use of the loophole results in a significantly greater loss of revenue to the government as a whole, particularly to the Social Security and Medicare trust funds. And the creation of shell companies in places such as the Cayman Islands to avoid taxes has long been attacked by members of Congress.

A Globe survey found that the practice is unusual enough that only one other ma jor contractor in Iraq said it does something similar.

"Failing to contribute to Social Security and Medicare thousands of times over isn't shielding the taxpayers they claim to protect, it's costing our citizens in the name of short-term corporate greed," said Senator John F. Kerry, a Massachusetts Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee who has introduced legislation to close loopholes for companies registering overseas.

With an estimated $16 billion in contracts, KBR is by far the largest contractor in Iraq, with eight times the work of its nearest competitor.

The no-bid contract it received in 2002 to rebuild Iraq's oil infrastructure and a multibillion-dollar contract to provide support services to troops have long drawn scrutiny because Vice President Dick Cheney was Halliburton's chief executive from 1995 until he joined the Republican ticket with President Bush in 2000.

The largest of the Cayman Islands shell companies - called Service Employers International Inc., which is now listed as having more than 20,000 workers in Iraq, according to KBR - was created two years before Cheney became Halliburton's chief executive. But a second Cayman Islands company called Overseas Administrative Services, which now is listed as the employer of 1,020 mostly managerial workers in Iraq, was established two months after Cheney's appointment.

Cheney's office at the White House referred questions to his personal lawyer, who did not return phone calls.

Heather Browne, a spokeswoman for KBR, acknowledged via e-mail that the two Cayman Islands companies were set up "in order to allow us to reduce certain tax obligations of the company and its employees."Social Security and Medicare taxes amount to 15.3 percent of each employees' salary, split evenly between the worker and the employer. While KBR's use of the shell companies saves workers their half of the taxes, it deprives them of future retirement benefits.

In addition, the practice enables KBR to avoid paying unemployment taxes in Texas, where the company is registered, amounting to between $20 and $559 per American employee per year, depending on the company's rate of turnover.

As a result, workers hired through the Cayman Island companies cannot receive unemployment assistance should they lose their jobs.

In interviews with more than a dozen KBR workers registered through the Cayman Islands companies, most said they did not realize that they had been employed by a foreign firm until they arrived in Iraq and were told by their foremen, or until they returned home and applied for unemployment benefits.

"They never explained it to us," said Arthur Faust, 57, who got a job loading convoys in Iraq in 2004 after putting his resume on KBRcareers.com and going to orientation with KBR officials in Houston.

But there is one circumstance in which KBR does claim the workers as its own: when it comes to receiving the legal immunity extended to employers working in Iraq.

In one previously unreported case, a group of Service Employers International workers accused KBR of knowingly exposing them to cancer-causing chemicals at an Iraqi water treatment plant. Under the Defense Base Act of 1941, a federal workers compensation law, employers working with the military have immunity in most cases from such employee lawsuits.

So when KBR lawyers argued that the workers were KBR employees, lawyers for the men objected; the case remains in arbitration.

"When it benefits them, KBR takes the position that these men really are employees," said Michael Doyle, the lawyer for nine American men who were allegedly exposed to the dangerous chemicals. "You don't get to take both positions."

Founded by two brothers in Texas in 1919, the construction firm of Brown & Root quickly became associated with some of the largest public-works projects of the early 20th century, from oil platforms to warships to dams that provided electricity to rural areas.

Its political clout, particularly with fellow Texan Lyndon Johnson, was legendary, and it became a major overseas contractor, building roads and ports during the Vietnam war.

Halliburton, a Houston-based oil conglomerate, acquired Brown & Root in 1962. And after the Vietnam cease-fire agreement in 1973, it all but stopped doing overseas military work for two decades.

But in 1991, during the Gulf War, Halliburton decided to try to revive its military business. The next year, Brown & Root won a $3.9 million contract from the Defense Department under Secretary Dick Cheney to develop contingency plans to support, feed, house, and maintain the US military in 13 hot spots around the world.hat small contract soon grew into a massive logistical-support contract under which the company did everything from building military camps to cooking meals and providing transportation for troops. Under the contract, the military agreed to reimburse Brown & Root for all expenses, and to pay a profit of between 1 and 9 percent, depending on performance.

In Somalia, starting in December 1992, Brown & Root employees helped US soldiers and UN workers dig wells and collect garbage, among many other tasks. The company quickly became the largest civilian employer in the country, with about 2,500 people on its payroll. Its headquarters in Texas had a "war room," where executives would get daily updates about events in Mogadishu.

Later the company would play similar roles supporting US troops in Haiti, Rwanda, Bosnia, Uzbekistan, and Afghanistan.

As its military work increased, Brown & Root sent more American workers overseas. Americans working and living abroad receive significant breaks on their income tax, but still must pay Social Security and Medicare taxes if they work for an American company. The reasoning is that such workers are likely to return to the United States and collect benefits, so they and their employers ought to help pay for them.

But the taxes drive up costs. A former Halliburton executive who was in a senior position at the company in the early 1990s said construction companies that avoid taxes by setting up foreign subsidiaries have obvious advantages in bidding for military contracts.

Payroll taxes can be a significant cost, he said, speaking on the condition of anonymity. "If you are bidding against [rival construction firms]

Service Employers International was set up in 1993, as Brown & Root was ramping up its roster of overseas workers. Two years later, the company set up Overseas Administrative Services, which serves more senior workers and provides a pension plan.

The parent company became Kellogg Brown & Root in 1998, when it joined with the oil-pipe manufacturer, M. W. Kellogg.

Around that time, KBR lost its exclusive contract to provide logistical support to the US military. But in 2001 it outbid DynCorp to win it back, by agreeing to a maximum profit of 3 percent of costs.

Then, in 2002, the firm received a secret contract to draw up plans to restore Iraq's oil production after the US-led invasion of Iraq. The Defense Department has said the firm was chosen mainly for its assets and expertise, not its ability to control costs.

Nonetheless, KBR's top competitors in Iraq do not appear to have gone to the same lengths to avoid taxes. Other top Iraq war contractors - including Bechtel, Parsons, Washington Group International, L-3 Communications,"It has been Fluor Corporation's policy to compensate our employees who are US citizens the same as if they worked in the geographic United States," said Keith Stephens, Fluor's director of global media relations. "With the exception of hardship and danger pay additives for work performed in Iraq, they receive the same benefits as their US-based colleagues, and Fluor pays or remits all required US taxes and payroll burdens, including FICA payments and unemployment insurance."

Only one other top contractor, the construction and logistics firm IAP Worldwide Services Inc., said it employs a "limited number" of Americans through an offshore subsidiary.

Officials at DynCorp, the company that KBR outbid for the logistics contract, did not return numerous calls.

KBR is now widely believed to be the largest private employer of foreigners in Iraq, and it hires twice as many workers through its Cayman Island subsidiaries as it does by direct hires. Service Employers International alone employs more than 20,000 truck drivers, electricians, accountants, and engineers, roughly half of whom are American, according to Browne, the KBR spokeswoman.

KBR declined to release salary information. But workers interviewed by the Globe who served in a range of jobs said they earned between $48,000 and $85,000 per year. If KBR's American workers averaged even as much as $63,000 per year, they and KBR would have owed more than $100 million per year in Social Security and Medicare taxes, split evenly between them. Over the course of the five-year war, their tax bill would have been more than $500 million.

In 2004, auditors with the Pentagon's Defense Contract Audit Agency questioned KBR about the two Cayman Island companies but ultimately made no complaint. The auditors told the Globe in an email exchange facilitated by Pentagon spokesman Lieutenant Colonel Brian Maka that any tax savings resulting from the offshore subsidiaries "are passed on" to the US military.

Browne, the KBR spokeswoman, said the loss to Social Security could eventually be offset by the fact that the workers will receive less money when they retire, since benefits are generally based on how much workers and their companies have paid into the system.

Medicare, however, does not reduce benefits for workers who don't contribute, and Browne acknowledged that KBR has not calculated the impact of its tax practices on the government as a whole.

She said KBR does not save money from the practice, since its contracts allow for its labor expenses to be reimbursed by the US military. But the practice gives KBR a competitive advantage over other contractors who pay their share of employment taxes.

And critics of tax loopholes note that the use of offshore shell companies to avoid payroll taxes places a greater burden on other taxpayers."The argument that by not paying taxes they are saving the government money is just absurd," said Robert McIntyre, director of Citizens for Tax Justice, a Washington advocacy group.

To the people listed as its workers, Service Employers International Inc. - known to them as SEII - remains something of a mystery.

"Does anybody know what or where in the Grand Cayman Islands SEII is located?" a recently returned worker wrote in a complaint about the company on JobVent.com, an employment website. He speculated that the office in the Cayman Islands must be "the size of a jail cell . . . with only a desk and chair."

In fact, the address on file at the Registry of Companies in the Cayman Islands leads to a nondescript building in the Grand Cayman business district that houses Trident Trust, one of the Caymans' largest offshore registered agents. Trident Trust collects $1,000 a year to forward mail and serve as KBR's representative on the island.

The real managers of Service Employers International work out of KBR's office in Dubai. KBR and Halliburton, which also moved to Dubai, severed ties last year.

Both KBR and the US military appear to regard Service Employers International and KBR interchangeably, except for tax purposes. According to the Defense Contract Auditing Agency, KBR bills the Service Employers workers as "direct labor costs," and charges almost the same amount for them as for direct hires.

The contract that workers sign in Houston before traveling to Iraq commits workers to abide by KBR's code of ethics and dispute-resolution mechanisms but states that the agreement is with Service Employers International.

Some workers said they were told that Service Employers International was just KBR's payroll company. Others mistook the name as a reference to the well-known, large union, Service Employees International.

Henry Bunting, a Houston man who served as a procurement officer for a KBR project in Iraq in 2003, said he first found out that he was working for a foreign subsidiary when he looked closely at his paycheck.

"Their whole mindset was deceit," Bunting said. He said that he wrote to KBR several times asking for a W-2 form so he could file his taxes, but that KBR never responded.

David Boiles, a truck driver in Iraq from 2004 to 2006, said that he realized he was working for Service Employers International when he arrived in Iraq and his foreman told him he was not a KBR employee, despite the fact that his military-issued identification card said "KBR."

"At first, I didn't believe him," Boiles said.

Danny Langford, a Texas pipe-fitter who was sent to work in a water treatment plant in southern Iraq in July 2003, said he, too, initially believed that he was an employee of KBR.But when he allegedly got ill from chemicals at the plant and was terminated that fall, he said, his application for unemployment compensation was rejected because he worked for a foreign company.

"Now, I don't know who I was working for," he said in a telephone interview.

For decades Congress has sought to crack down on corporations that use offshore subsidiaries to lower their taxes, but most of the debates have focused on schemes that reduce corporate income taxes, not payroll taxes. Last year a Senate subcommittee estimated that US corporations avoid paying $30 and $60 billion annually in income taxes by using offshore tax havens.

Senators Carl Levin, a Michigan Democrat; Barack Obama, an Illinois Democrat; and Norm Coleman, a Minnesota Republican, are trying to pass the Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act, which would give the US Treasury Department the authority to take special measures against foreign jurisdictions that impede US tax enforcement.

American companies that evade payroll taxes face fines or other criminal penalties. The use of foreign subsidiaries to avoid payroll taxes, while allowed by the Defense Department, may still be subject to challenge by the Internal Revenue Service, according to Eric Toder, a former director of the office of research for the IRS.

Toder said the IRS could try to take action against a firm if the sole purpose of setting up an offshore subsidiary was to reduce tax liability. The practice could become a more costly problem in the future, Toder said, as an increasing number of American companies register subsidiaries overseas and bring American employees to work abroad.

"It obviously looks unseemly where you have a situation where, if you did it in a straightforward way, they would pay payroll taxes," Toder said. "If this becomes the norm, and other companies do that as well, it could further erode the tax base."

Peter Singer, a specialist in the outsourcing of military functions at the liberal-leaning Brookings Institution, said the practice will probably attract more scrutiny in the future, as the military expands its outsourcing and as workplaces become increasingly global.

"It is fascinating and troubling at the same time," Singer said. "If you are an executive in a company, you are thinking: 'Wow. Cash savings and a potential loophole from certain domestic laws, lawsuits, and taxes. It's win-win.' But if you are a US taxpayer, it is not a positive synergy."

Globe correspondents Stephanie Vallejo and Matt Negrin contributed to this report.![]()

| |

History suggests copyright crusade is a lost cause

File-sharing and property rights

Recently, the Los Angeles Times's Jon Healey kicked off a new round in the long-running debate about the moral status of file-sharing. Critics of the practice analogize copyrights to property rights, suggesting that file-sharing is a form of theft. Property rights have emotional resonance across the political spectrum. As a result, those who want to increase the power of copyright owners have tended to stress the similarities between copyrights and property rights. In contrast, those who who favor less restrictive copyright laws, as well as those who oppose copyright altogether, have resisted this analogy.

In a sense, this is obviously just a semantic dispute. But there are also important philosophical and legal issues underlying these arguments. As a strong supporter of property rights, I'm very interested in the similarities and differences between copyrights and traditional property rights.

Two arguments for property rights

To evaluate the analogy more carefully, it's necessary to consider why property rights are needed in the first place. There are two basic arguments, which we might call the scarcity argument and the reward argument. The scarcity argument suggests that property rights are needed to ensure an efficient allocation of scarce resources. When a resource lacks a clear owner, there is a temptation to overuse it. The classic example of this is the tragedy of the commons, in which communally-owned pasture land is over-grazed to the detriment of all of the field's users. The tragedy of the commons can often be solved by dividing the land up into discrete plots, each owned by a single individual who will be motivated to take good care of it.

The scarcity argument focuses on the efficient use of existing resources. In contrast, the reward argument focuses on the creation of new resources. It says that people will under-produce valuable resources if they aren't allowed to keep what they produce. For example, a farmer is far less likely to plant crops in the spring if he won't be able to prevent others from harvesting them in the fall.

Both of these arguments are good reasons for property rights in physical objects. But only the reward argument seems to apply to copyright. As Mike Masnick has noted, once an information good has been produced, it can be reproduced an unlimited number of times without diminishing its value. Opponents of copyright emphasize the scarcity argument to illustrate the differences between copyright and traditional property rights.

Of course, the reward argument assumes that particular classes of creative works wouldn't be adequately supplied in the absence of copyright protection. This seems to be true for at least some categories of copyrighted works. It is hard to imagine, for example, that Hollywood studios would spend tens of millions of dollars producing a new blockbuster if the law didn't grant them exclusive rights in its commercial reproduction.

Yet in many cases, it's far from clear that copyright is necessary for all categories of creative works. For example, I doubt there would be a shortage of photographs without copyright protections for photographers. Similarly, there is no shortage of garage bands producing music with no realistic expectation of making music for a living. It's not hard to imagine that there would be continue to be plenty of music in the absence of copyright protection for musical works.

The mystery of copyright

If we take the analogy between copyright and property rights seriously, it has some implications that advocates of strong copyright may not like. The copyright system is currently undergoing rapid changes as technology undermines old business models and enforcement regimes. Some aspects of copyright law are widely ignored and evaded, and efforts to strictly enforce the law have sparked widespread outrage. If we want to take the property rights analogy seriously, it doesn't make sense to compare today's chaotic copyright regime to the stable, orderly, and universally accepted property rights system we have today. Rather, the right comparison is to the American property rights system at a time when it, too, faced rapid changes and serious challenges to its legitimacy.

If we take the analogy between copyright and property rights seriously, it has some implications that advocates of strong copyright may not like. The copyright system is currently undergoing rapid changes as technology undermines old business models and enforcement regimes. Some aspects of copyright law are widely ignored and evaded, and efforts to strictly enforce the law have sparked widespread outrage. If we want to take the property rights analogy seriously, it doesn't make sense to compare today's chaotic copyright regime to the stable, orderly, and universally accepted property rights system we have today. Rather, the right comparison is to the American property rights system at a time when it, too, faced rapid changes and serious challenges to its legitimacy.

In his widely-cited 2000 book The Mystery of Capital, economist Hernando de Soto looked back at the formative years of property regimes around the world. While de Soto himself never mentions copyright law, the conflicts he describes have striking parallels to today's copyright debate.

21st century virtual squatters?

The American property system is based on the British common law system, but colonists quickly discovered that British property law was inadequate to the realities of the New World. In England, land was scarce, and titles were well-established. The American colonies, in contrast, had an abundance of land but poorly-defined boundaries and inadequate record-keeping. As a result, squatting became extremely common. Landless Americans would move to the frontier, clear some land, and begin building on it without first securing a property title.

This was illegal, and governments worked hard to prevent it. The resulting conflicts made today's battles over file-sharing look tame. In 1786, when Massachusetts tried to eject squatters in Maine (a Massachusetts territory at the time) the result was what one historian describes as "something like open warfare." Squatters refused to pay for their land or vacate it, and the government tried to forcibly evict them. One sheriff was killed trying to evict a squatter, and juries refused to convict the accused murderer.

This was illegal, and governments worked hard to prevent it. The resulting conflicts made today's battles over file-sharing look tame. In 1786, when Massachusetts tried to eject squatters in Maine (a Massachusetts territory at the time) the result was what one historian describes as "something like open warfare." Squatters refused to pay for their land or vacate it, and the government tried to forcibly evict them. One sheriff was killed trying to evict a squatter, and juries refused to convict the accused murderer.

The newly-created federal government soon joined the war against the squatters. The 1787 Northwest Ordinance established procedures for purchasing Western land from the federal government, but these laws were widely ignored by squatters who lacked the funds and the legal expertise to participate. In 1807 Congress provided for fines and imprisonment for squatters who refused to vacate land they had settled without federal permission.

As Congress and state governments passed more legislation to deal with squatters, the law only became more chaotic. As de Soto describes it:

Between 1785 and 1890, the United States Congress passed more than five hundred different laws to reform the property system, ostensibly based on the Jeffersonian ideal of putting property into the hands of private citizens. The complicated procedures associated with these laws, however, often hampered this goal... By 1820, the original U.S. property system was in such disarray that the Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story wrote: "Ages will probably lapse before litigations founded on [the U.S. property laws] will be closed."

The property rights quandary was ultimately resolved not by harsher enforcement of existing laws, but by adjusting the property system to recognize the realities on the frontier. Politicians from Western states were more sympathetic to squatters, many of whom were their constituents, and they pressed for their claims to be recognized by the legal systems. Squatters had created informal mechanisms for delineating and enforcing their claims, and over the course of the 19th century, governments increasingly extended formal recognition to these arrangements.

Lessons for copyright policy

There are some obvious parallels to the contemporary file-sharing debate. Like squatters of old, many ordinary users find copyright law bewildering and are frustrated by the arbitrary restrictions it imposes. Customers wanting to rip their DVD collections to their computers, download music they can play on any device, or incorporate copyrighted works into original creative works find that there is no straightforward, legal way to do these things.

The dismal state of copyright law is a reflection of rapid technological change. In the 20th century, the copyright system was geared toward the needs of the large, capital-intensive firms—movie studios, book publishers, newspapers, record labels—that produced the bulk of the copyrighted works. Because few individuals could afford their own printing presses or broadcasting equipment, 20th-century copyright law hardly ever impacted the actions of ordinary Americans. The large firms that were subject to copyright law could afford to hire lawyers to advise them on what the law required.

But the emergence of the Internet and other digital technologies have brought the technologies of wide-scale content creation and distribution to the masses. As a result, millions of people suddenly have to worry about copyright issues that previously applied only to commercial firms. Many of them find the requirements of copyright law unreasonable, and they have reacted by simply ignoring it.

Getting users to stop sharing files and circumventing DRM is likely to prove just as hopeless as getting squatters to leave their homes. There are now millions of people who think nothing of evading the law, and there are simply not enough courts to try more than a tiny fraction of them. Sooner or later, Congress will have to do for the copyright system what it did for property rights in the 19th century: change the law to bring it back into line with peoples' moral intuitions.

Getting users to stop sharing files and circumventing DRM is likely to prove just as hopeless as getting squatters to leave their homes. There are now millions of people who think nothing of evading the law, and there are simply not enough courts to try more than a tiny fraction of them. Sooner or later, Congress will have to do for the copyright system what it did for property rights in the 19th century: change the law to bring it back into line with peoples' moral intuitions.

The fundamental lesson is that property rights are not—and never have been—created by Congressional fiat. Property rights emerge spontaneously from the social fabric of a community. The job of the legislature is not to create a property system from scratch, but to formalize the property arrangements that communities have already agreed upon among themselves. A system of property rights will only be effective if it is widely viewed as legitimate.

If copyrights are a form of property right, then the history of American property rights provides clues about how the copyright system will need to evolve in the future. It suggests that Congress's current strategy of imposing ever more draconian penalties for breaking laws that lack broad public support is a recipe for failure. Congress may be forced to concede, as it did two centuries ago, that property law must accommodate the actions of ordinary Americans, and not the other way around.

Similarly, major copyright owners might learn something from this history. Ordinary consumers are more likely to respect copyright if they view its restrictions as reasonable. Rather than trying to browbeat consumers into accepting highly restrictive copyright policies, they might find it worthwhile to adjust their business strategies to provide their customers with legal ways to do things they're likely to do anyway. The labels' contract with Imeem is a good model, as it, for the first time, gave consumers the ability to share music with their friends in exchange for a cut of ad revenue. In the long run, accommodating customer demands is likely to be a more successful business strategy than trying to enforce every provision of copyright law to the hilt.