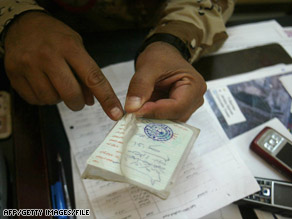

An Iraqi army officer shows a fake ID taken off an al Qaeda suspect in Mosul in May.

BAGHDAD, Iraq (CNN) -- With Christmas 2005 approaching, the princes of al Qaeda's western command were gathering. They'd been summoned for something special: to plot a three-month campaign of coordinated suicide, rocket and infantry attacks on American bases, checkpoints and Iraqi army positions.

In al Qaeda in Iraq's hierarchy, prince designates a senior leader, and these princes had been gathered by the most senior among them, the prince of Anbar province itself.

This commander, his name not recorded in al Qaeda's summaries of the meetings and referred to only by rank, spent that December fleshing out his vision for the wave of assaults with the gathered subordinates who would lead his combat brigades.

The gathering was a council of war, its meetings remarkably detailed in al Qaeda records. In minutes of their secretive meetings, a grim notation was made: Operation Desert Shield had been approved and would "hopefully commence in mid-January 2006."With the operation approved, the prince of Anbar listened to the briefings of his assembled commanders: the chairmen of both his military and his security committees, plus the various princes from the sectors he controlled -- Falluja, Ramadi, Anbar-West and Anbar-Central. All boundary demarcations strikingly similar to those used by the American soldiers they were fighting.

The overall plan, too, was similar to any that the U.S. army would devise. First, the military committee chairman outlined plans to seal off the U.S. targets as much as possible by harassing supply lines, damaging bridges and targeting helicopters and their landing zones, in a bid to restrict reinforcement or resupply.

Then the security chairman spoke of the need to maintain strict "operational security," ordaining that only the princes, or leaders, involved in the meetings be informed of the grand strategy, leaving cell leaders and battalion commanders to believe their individual attacks were being launched in isolation.

All this would be Phase I, a precursor to the 90 days of attacks of Phase II, to be timed across not just Anbar but across much of Sunni Iraq to stretch and distract America's war commander, Gen. David Petraeus.

Flowing from the memo approving Operation Desert Shield, a stream of reports follow.

On January 7, 2006, a memo called for Iraqis who'd infiltrated various U.S. bases to conduct site surveys to help identify the camps that would be hit. The two-page note also spoke of placing ammunition stores well in advance of the attacks so the fighters could resort to them during the battles.

The January memo also commented on training and rehearsals for the offensive and the extraction routes their fighters would use after the attacks, and it dictated the need to obtain pledges from the foot soldiers of their willingness to die.

In another memo, reports were compiled from al Qaeda field commanders recommending which U.S. Army and Marine bases or Iraqi checkpoints or police stations should be targeted. Baghdad International Airport was one of the targets named. Beside each entry were notes on weapons each target would require: Grad surface-to-surface missiles, Katyusha rockets, roadside bombs and suicide bombers.

Phase II, the 90-day offensive, commenced around March 2006, with al Qaeda's records from Anbar that month reading like a litany of what the U.S. Army would call AARs, or After Action Reports, listing each attack's successes and failures. It also noted the losses suffered by both al Qaeda or, in what Americans would call Battle Damage Assessments, the losses suffered by the coalition.

Al Qaeda's folder on Operation Desert Shield expresses the depth, structure and measure of its military command. It is perhaps the most compelling illustration of how al Qaeda works.

Yet the Desert Shield folder is but one found among the thousands of pages of records, letters, lists and hundreds of videos held in the headquarters of al Qaeda's security prince for Anbar province, a man referred to in secret correspondence as Faris Abu Azzam.

After he was killed 18 months ago, Faris' computers and filing cabinets were captured by anti-al Qaeda fighters from a U.S-backed militia, or Awakening Council (the militias made up of former Sunni insurgents, now on the U.S. payroll and praised by President Bush for gutting al Qaeda in Iraq). The Awakening militiamen handed the massive haul of al Qaeda materials to both their U.S handlers from the Navy, Marine Corps and Army, and to CNN.

In all, these Anbar files form the largest collection of al Qaeda in Iraq materials to ever fall into civilian hands, giving an insight into the organization that few but its members or Western intelligence agents have ever seen.

Rear Adm. Patrick Driscoll, the American military's spokesman in Baghdad, says the document trove is unique, "a kind of comprehensive snapshot" of al-Qaeda during its peak.

"It reveals," Driscoll said, "first of all, a pretty robust command and control system, if you will. I was kind of surprised when I saw the degree of documentation for everything -- pay records, those kind of things -- and that [al Qaeda in Iraq] was obviously a well-established network."

That network is now under enormous stress, primarily from the more than 100,000 nationalist insurgents who formed the Awakening Council militias and initiated an extremely effective assassination program against al Qaeda, but also from recent U.S. and Iraqi government strikes into their strongholds.

As a result, says Lt. Col. Tim Albers, the coalition's director of military intelligence for Baghdad, "al Qaeda in Iraq is fighting to stay relevant."

So, what do these captured documents from 2006 tell us about al Qaeda in Iraq today? A lot, according to a senior U.S. intelligence analyst in Iraq, who cannot be named because of the sensitivity of his position.

"We're still finding documents like these throughout the country, but I would say that's starting to lessen in amount as the organization shrinks," the analyst said.

The al Qaeda command mechanism and discipline seen in the documents, he said, persist.

"The hard-core senior leadership is still trucking along, and there are always going to be internal communications, documents and videos," he said.

With as many as six suicide attacks and three car bombings in the past 10 days in Iraq (including one attack that killed a U.S. soldier and wounded 18 others), Driscoll agrees the picture the documents paint of a well-oiled, bureaucratic organization is relevant today.

"Certainly, we see that in several different ways how they communicate ... as they've got to be able to talk to their troops in the field to maintain morale, especially when we're pursuing them very aggressively," Driscoll said.

Be it then, in 2006, or be it now, al Qaeda in Iraq is nothing if not bureaucratic.

Included in the headquarters of the security prince, Faris, are bundles of pay sheets for entire brigades, hundreds of men carved into infantry battalions and a fire support -- or rocket and mortar -- battalion. To join those ranks, recruits had to complete membership forms.

"These are the application forms filled in by the people who join al Qaeda," Abu Saif said, holding one of the documents obtained by CNN. Until recently, Abu Saif was himself a senior-level al Qaeda commander.

"They took information about [the recruits], and if the applicant lied about something -- because they were investigated -- they would whip him," Abu Saif said.

Induction into al Qaeda, he said, would take up to four months. In one case, Abu Saif recounted, an applicant lived for four months at the home of what he thought was a local supporter of the organization providing a safe house. Finally accepted and called to a cell leaders' meeting, he discovered that his host was actually a senior recruiter who'd been studying his every move for those four months.

Al Qaeda's bookkeeping was orderly and expansive: death lists of opponents, rosters of prisoners al Qaeda was holding, along with the verdicts and sentences (normally execution) the prisoners received, plus phone numbers from a telephone exchange of those who'd called the American tip line to inform on insurgents, and motor pool records of vehicle roadworthiness.

And there are telling papers with a window into al Qaeda's ability to spy on its pursuers. One is a document leaked from the Ministry of Interior naming all the foreign fighters held in government prisons. Other documents discuss lessons al Qaeda learned from its members captured by American forces and either released or still in U.S.-run prisons. The leadership studied and discussed the nature of the American interrogations, the questioning techniques used and the methods that had been employed to ensnare its men.

And an Iraqi contractor even wrote the Anbar security prince, asking permission to oversee a $600,000 building project on a U.S. base, attaching the architectural drawings of the bunkers he was to make, with an offer to spy and steal weapons during the construction.

It seems al Qaeda in Iraq is almost as pedantically bureaucratic as was Saddam Hussein's Ba'ath party, a trait that really shouldn't surprise.

Though al Qaeda was denied a foothold in Iraq during Hussein's regime, with its ideology unappealing to the mostly secular professional military officers in the former dictator's armies, that has now changed.

According to the internal al Qaeda correspondence in the files, Iraqis have taken to, and effectively run, al Qaeda in Iraq. Foreign fighters' roles seem mostly relegated to the canon fodder of suicide attacks.

Though the upper tiers of the organization are still dominated by non-Iraqis, in Anbar, at least, all the princes and brigade and battalion commanders are homegrown.

"Correct. They're all Iraqis," Abu Saif said. "In my house [one time], there were about 18 Arab fighters under Iraqi commander Omar Hadid, mercy of God upon him, and the [foreigners] did not object, they just did their duty."

That Iraqification of the network is what perhaps enabled al Qaeda to foresee its demise years before the Americans did.

Documents from 2005 and 2006 show that top-ranking leaders feared the imposition of strict religious law and brutal tactics were turning their popular support base against them.

One memorandum from three years ago warned executions of traitors and sinners condemned by religious courts "were being carried out in the wrong way, in a semi-public way, so a lot of families are threatening revenge, and this is now a dangerous intelligence situation."

That awareness led al Qaeda to start killing tribesmen and nationalist insurgents wherever they began to rally against it, long before America ever realized that it had potential allies to turn to.

Yet those same practices that accelerated al Qaeda in Iraq's undoing were breathtakingly documented.

In a vein similar to the Khmer Rouge's grisly accounting of its torture victims, within the files of one al Qaeda headquarters in Anbar alone was a library of 80 execution videos, mostly beheadings, none of which had been distributed or released on the Internet. And all were filmed after al Qaeda in Iraq ended its policy of broadcasting such horrors.

So why keep filming? According to former member Abu Saif and the senior U.S. intelligence analyst, to verify the deaths to al Qaeda superiors and to justify continued funding and support.

The videos also bear insight into al Qaeda's media units. Raw video among the catalog of beheadings shows how al Qaeda's editing skills hide not just its members' faces (caught in candid moments on the un-edited films) but also their failures.

When three Russian diplomats were kidnapped and killed in June 2006, a well-polished propaganda piece was released. It showed two diplomats being gruesomely beheaded, and yet the third diplomat was shot with a pistol, in a different location. The full video of the slayings answers why.

Though bound and blindfolded, the third diplomat struggled so defiantly that his ailing executioners could not draw their knife across his throat. In the horrific and chaotic scenes, the faces of his killer and the cameraman are seen.

And those scenes, like the intricacy of the prince of Anbar's planning and internal analysis of Operation Desert Shield, reveal an al Qaeda in Iraq that the world still barely knows.Original here

No comments:

Post a Comment